A New Face: The Greatest Investment You Could Ever Make?

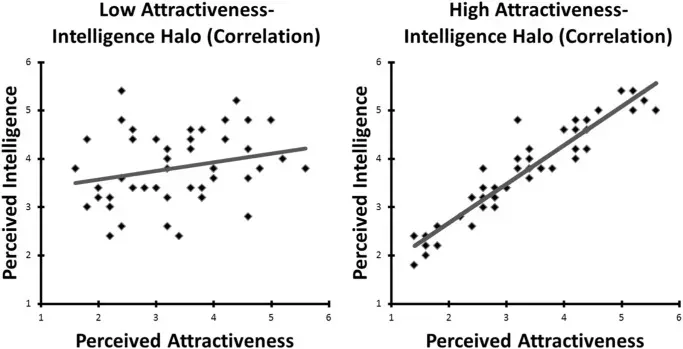

I was introduced to the concept of the Halo Effect in a high school psychology course. For those unfamiliar, the halo effect is a cognitive bias where known positive traits are assumed to ‘transfer over’ to unknown traits. The most common application of the term is in the context of attractiveness. Attractiveness is an immediately visible trait, and so attractive people are often assumed to be kinder, harder working, etc. While one might wish this factor did not have much influence past initial dating stages or friendships, attractiveness correlates with perceived intelligence and even criminal sentencing.

Occasional reminders of these connections would surface online, and at some point I couldn’t help but think: Are there situations in which getting Cosmetic Surgery could be the greatest personal investment you could make?

I want to make a quick note here that this is purely an intellectual exercise. Major surgery is a deeply personal decision, and this post should not strongly convince you either way. This is, more than anything, just an exploration of how much of our modern world is shaped by primal psychological instincts, and how much one could potentially use medical interventions to get a leg up.

I’ll break this exploration into a few parts. First, we must examine exactly how much attractiveness matters financially. For the purposes of this post, I will focus on lifetime earnings; more subtle social effects are outside the scope of this piece. Secondly, we must look at how much contemporary cosmetic surgeries affect perceived attractiveness. Lastly, we can look at the cost of surgery as it compares to changes in perceived attractiveness and eventual lifetime earnings. This rough figure could then be compared to other forms of investment, such as furthering your education, job-specific training, or traditional stocks.

- The Beauty Premium - How much does beauty pay?

The foundational text for this section is Hamermesh's Beauty Pays. The widely quoted finding from this book is that there is both a "Beauty Premium" and a "Plainness Penalty." Essentially, attractive individuals tend to earn more than average-looking people, and less attractive people tend to earn less than average people, respectively. Hamermesh suggests that attractive people earn between 3-8% more than their average counterparts, while less attractive people earn between 5-10% less. At the margins, this suggests that an attractive and a less attractive person may have up to an 18% difference in salary. For our future purposes, though, we might consider only the difference in either direction compared to average. We have not looked into cosmetic surgery yet, but a conservative estimate might assume that cosmetic surgery could take someone from less attractive to average (recouping the 5-10% plainness penalty) or from average to attractive (gaining the 3-8% beauty premium), rather than assuming cosmetic surgery could typically move someone across the entire attractiveness spectrum.

So, we have this economic premium based on looks, calculated as a percentage. I am going to assume that people who engage in the long-term pro-and-con thinking necessary to consider Cosmetic Surgery as an Investment have at least a bachelor's degree. A common estimate places average lifetime earnings with a bachelor's degree at around $2.3 million. Using Hamermesh's percentage ranges, being attractive would net you an additional 69k−184k, while the earnings deficit from being less attractive is 115k−230k compared to average. The maximum potential lifetime financial gain difference from moving from less attractive to very attractive could approach $414k.

This is just based on averages. If these percentage differences hold roughly at different levels of earning, then the absolute dollar impact makes attractiveness an even more high-impact factor the more an individual earns.

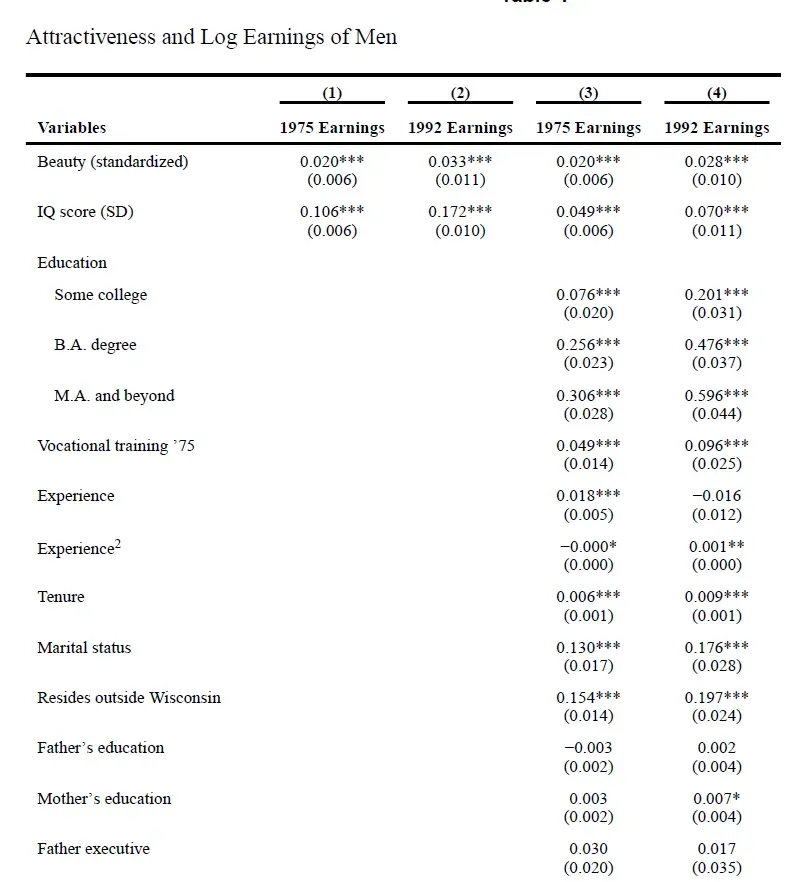

It’s necessary to look at sources outside just this one book. Scholz & Sicinski (2015) used longitudinal data to control for other variables and isolate the relationship between attractiveness and earnings. They found a persistent positive correlation between facial attractiveness (rated from high school photos) in young adulthood and earnings decades later. This premium remained statistically significant even after controlling for IQ. Even including controls such as marital status, family background, and education still left attractiveness as a significant, positively correlated trait. A one standard deviation increase in attractiveness was associated with 2%-3.3% higher earnings decades later (measurements from the 70’s and 90’s, respectively.)

Pfeifer (2011) examined interviewer-rated attractiveness in relation to wages and employability in Germany. He found that a one-point increase on an 11-point scale was related to roughly a 3% higher chance of being employed and a 3% higher wage when employed. He also suggests that these differences exist across the entire wage distribution, strengthening the earlier point that enhancing attractiveness could potentially be a stronger investment the more money you make. To be clear, this part of the finding was specifically in Germany, and as the wage distribution is greater in the US than there, it may not be as even across the distribution.

We can quickly look at potential mechanisms. Scholz & Sicinski found that attractiveness did correlate with confidence proxies and extroversion, but controlling for these factors still showed a relationship between attractiveness and pay. Pfeifer notes that it is specifically interviewer rated attractiveness score that correlates, not self-rated scores, suggesting confidence is not the feature being measured here. Hamermesh has a few main theories, mainly that either Customers discriminate based on looks or Employers discriminate based on looks, due to beauty correlating with positive traits (Halo effect). Some studies also find correlations between height and weight and wages, but facial attractiveness appears to be an independent feature as most studies control for BMI.In an age of fat removal and GLP-1 agonists, weight can also be a modifiable feature. Plenty of studies (Cawley 2004, Averett & Korenman 1996) do find a negative correlation between obesity and wages, particularly for women. However, I find it more interesting to focus specifically on facial attractiveness here. While the benefits of health and fitness often associated with weight management are widely understood, the mechanisms linking weight to wages can be complex, involving direct health factors alongside social perception. Concentrating on facial attractiveness allows a clearer look at the impact of the 'halo effect' and social signaling itself.

Multiple sources suggest there is a statistically significant difference in earnings based on attractiveness. It is not an overwhelming number, typically falling within single-digit percentages per standard deviation increase in attractiveness. Between these 3 sources, a reasonable working estimate might be around a 3-4% difference per standard deviation. Considering Hamermesh's point that the penalty may be larger towards the bottom, let's proceed with working estimates of a 5% earnings deficit between less attractive and average, and a 3% premium between average and attractive. Having established this financial differential, we now need to look into whether cosmetic surgery can actually make you perceived as more attractive.

- Surgical Enhancement - Measuring Impact of the scalpel on facial attractiveness

We have established now that there is some relationship between facial attractiveness and wages. We must ask a second, slightly less obvious question before we can look into surgery as investment: Can cosmetic surgery verifiably increase perceived attractiveness or related positive traits in a way that might tap into that premium? I must note here that many of these studies use observer ratings of before and after photos, and the selection of these photos or results may be cherry picked, especially if the researchers financially benefit from a positive public perception of cosmetic surgery.

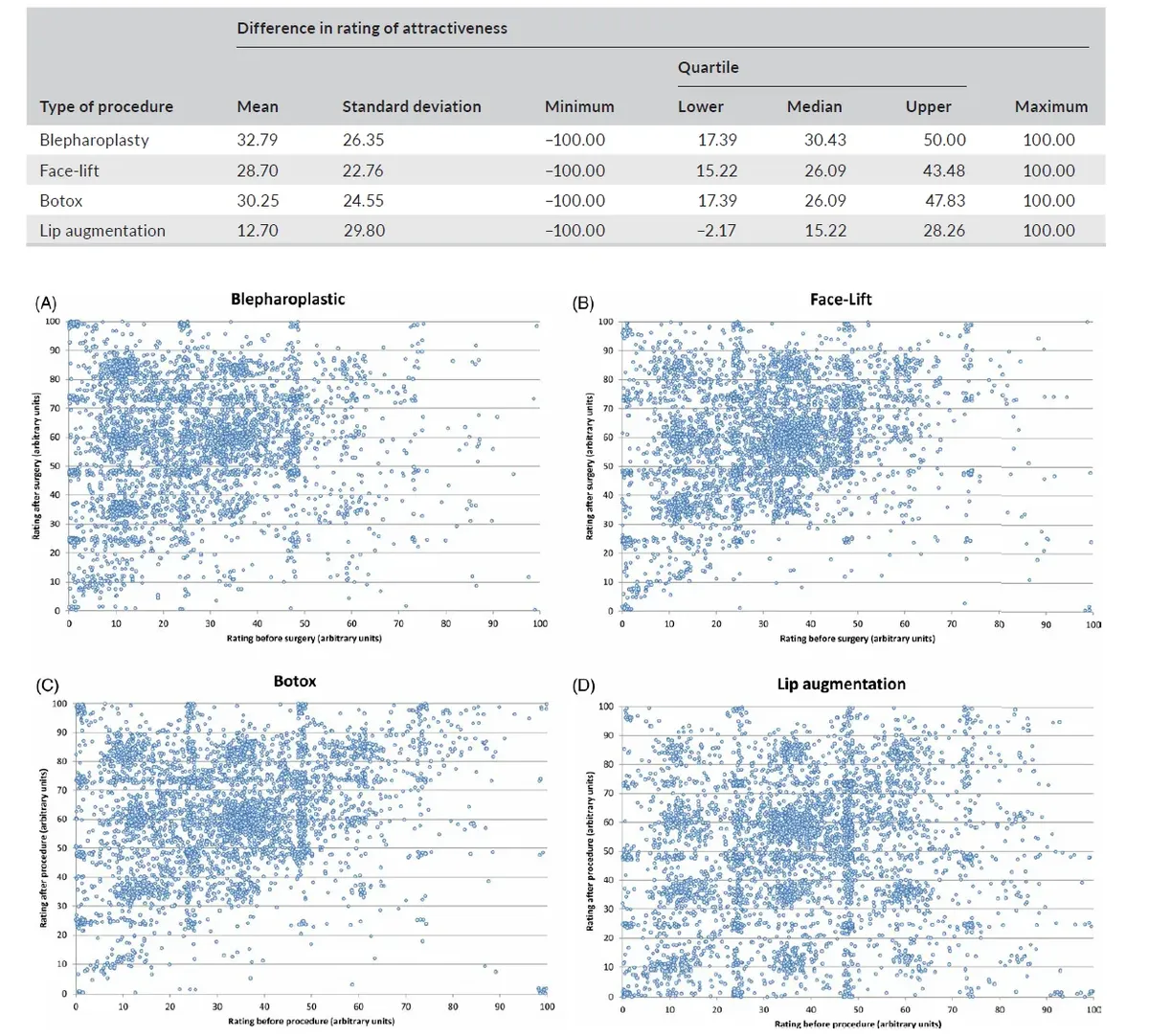

Przylipiak et al. (2019) takes 167 untrained observers, to look at before and after photos of 54 patients and rank them on a 100 point Arbitrary Unit scale and looks at 4 common surgeries (Blepharoplasty/ Eyelid Surgery, Face-Lift, Botox, and Lip Augmentation). Below is the chart, showing Eyelid surgery had the greatest improvement, followed by Botox, then Face-Lift, and finally Lip augmentation.

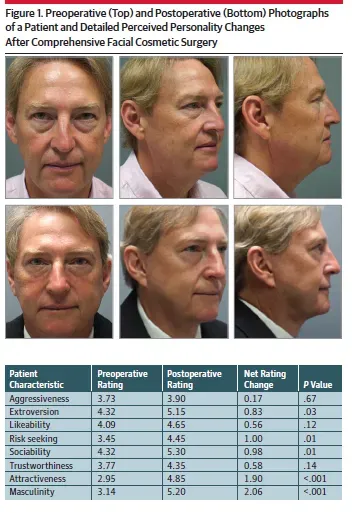

The quick way to parse this chart is to imagine a diagonal line from the bottom left corner to the top right corner. Every point above this line is someone who thought the after photo looked better than the before photo. Every point below this line is someone who thought the subject looked better before (sorry lip augmentation). The grid structure you see if you squint your eyes is due to vote clustering around whole numbers. The Vertical lines at 50 and slightly less at 25 are people really strongly rounding off their before votes to clear numbers. This doesn’t seem like much to worry about.Anecdotally, looking at before and after images of Blepharoplasty, it’s clear to me that it isn’t moving anyone who is average looking into the above average category. However on some people it is a clear improvement, and it definitely moves some below average firmly into the average range.Parsa et al. (2019) looks at something related to our initial claims of the Halo Effect: perceived personality traits before and after cosmetic surgery in men. 24 male patients with a variety of singular or comprehensive facial surgeries, ranked by 145 observers on a 7 point likert scale.

This is a photo example of someone who has had comprehensive facial surgery. Looking only at features with significant p values, perceived extroversion, risk seeking, sociability, attractiveness, and masculinity go up a significant amount. This man has a 64% improvement in perceived attractiveness. However, this is obviously an older gentleman. It may be the case that the older you are the greater the attractiveness gains from cosmetic surgery. However, the older you are the less time you have to make gains from being more attractive. Unfortunately I cannot find research on this topic specifically, otherwise we could attempt to calculate exactly when is the optimal age to get cosmetic surgery.

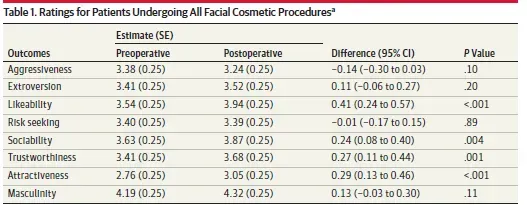

Looking at the comprehensive facial procedure chart, attractiveness goes up by 10%, similar to trustworthiness, sociability, and likeability. Notably, masculinity only shows statistical significance in the case of a neck lift, and chin augmentation has no independent correlation with any trait improvement.

So, it is hard to say exactly how much change occurs in perceived attractiveness due to cosmetic surgery, due to a lack of ability to translate between arbitrary units of many different studies and the fact that greater before and after photos may be chosen for the purposes of these studies. However, I think we can clearly say that cosmetic surgery can have a measurable positive impact on facial attractiveness.

- Calculating ROI

So lets package this together. The last piece of our conceptual puzzle piece is the cost of cosmetic surgery. The financial outlay varies significantly by procedure. Based on 2022 Aesthetic Plastic Surgery National Databank Statistics, average surgeon fees include:

Blepharoplasty (Eyelid Surgery): ~$4,838

Facelift: ~$9,679

Rhinoplasty: ~$5,999

Botox (per session, not surgery): ~$196

In the first part we made the rough assumption that a standard deviation is worth 5% if going from below average to average, and 3% if going from average to above average. To simplify once again, we can pick our original 2.3 million dollar lifetime earnings, and say that 92k (4%) is our expected payment from each standard deviation. The problem is that while we can show that you can get a 30 point Arbitrary Unity jump on a 100 scale, or a .3 point jump on a 7 point scale, we cannot track that clearly as a percentage of our 92k. So first, we can calculate exactly how much of this 92k (what percentage of one standard deviation) would each procedure have to capture to break even.

Blepharoplasty: ($4,838 / $92,000) * 100% ≈ 5.3%

Facelift: ($9,679 / $92,000) * 100% ≈ 10.5%

Rhinoplasty: ($5,999 / $92,000) * 100% ≈ 6.5%

So a blepharoplasty would only have to improve your facial attractiveness by 5.3% of 1 SD to pay itself off. If we assume that facial attractiveness can be measured on a 10 point scale, with an average of 5.5 and a standard deviation of roughly 1.5, then we can say that a Blepharoplasty will pay itself off if it can turn you from a 5.5/10 to a 5.575/10. I find that very likely. If we look at the original Arbitrary Unit gain of Blepharoplasty, with a mean gain of 33 points, and take the standard deviation of an evenly distributed 100 point scale to be about 30, then it roughly maps to a blepharoplasty giving a 1 SD boost. In this case, Blepharoplasty would be a 1900% ROI.Since the gains are evenly distributed across time, there actually isn’t anything stopping you from using your gains from attractiveness to make larger gains in other instruments. You could add all of your gains from your higher attractive wages to your retirement account as greater principle.There are problems with our calculations of course, beyond just the initial amount of speculation. They are highly weighted by many different variables. ‘How much attractiveness is worth’ and ‘How much does surgery improve your attractiveness’ are both very important features in these calculations that vary EXTREMELY based on individuals. Like we’ve established, going from unattractive to average probably has greater weight. Additionally, if you are considered unattractive because of a single specific feature, then your gains from surgical intervention on that feature is going to be much greater than someone who has a few issues with many different parts. Additionally, if you do no customer facing at all, or if your career path is almost entirely based on measurable technical ability, the value of each point of attractiveness means significantly less to you.Given these limitations, we should view this analysis as an interesting thought experiment to explore strange economic dynamics. This has all been highly speculative, and I once again should note that this isn’t to be taken as advice, financial or personal. There are many avenues towards more money, and it is interesting to look into what Alpha is lying around unanalyzed, no matter how strange it is.