Design Optimization: Soulless or Solution?

Christopher Alexander suggests that a good design is not a matter of artistic ability or design intuition but rather that a form be a ‘good fit’ for its context. Making a good fit is not a matter of listing out all the positive qualities that the form could have and making sure that it has all of them, but rather listing out the negative qualities and removing them. This philosophy begins to turn the project of design into something more akin to a mathematical model.

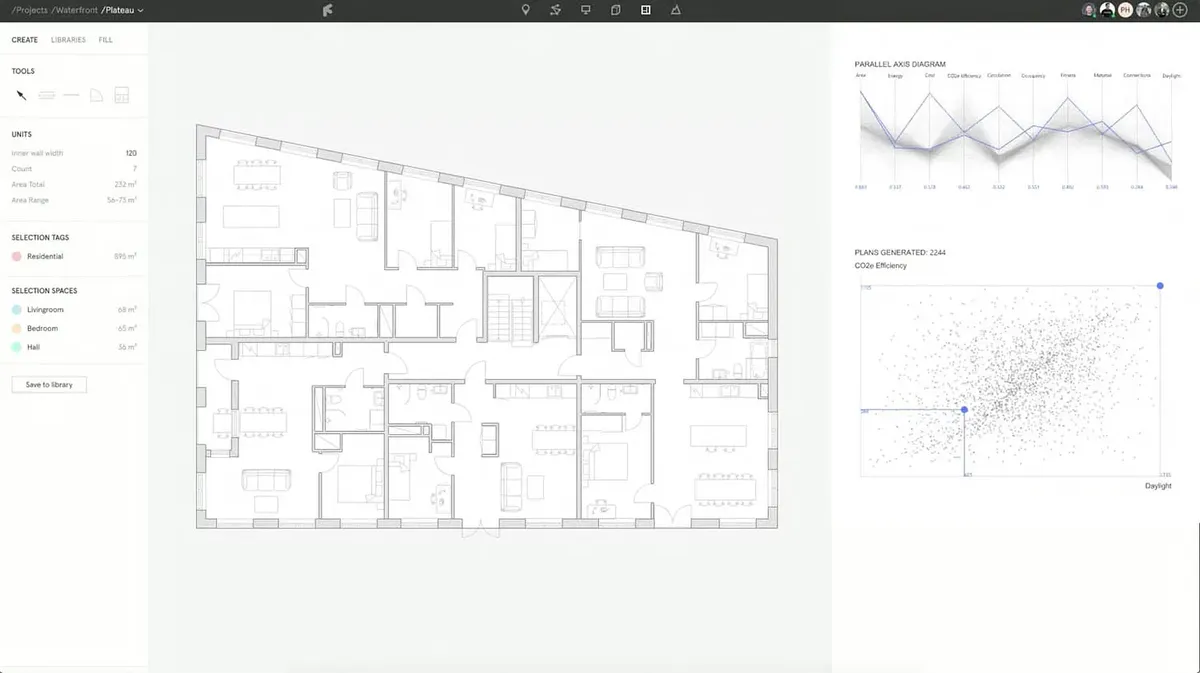

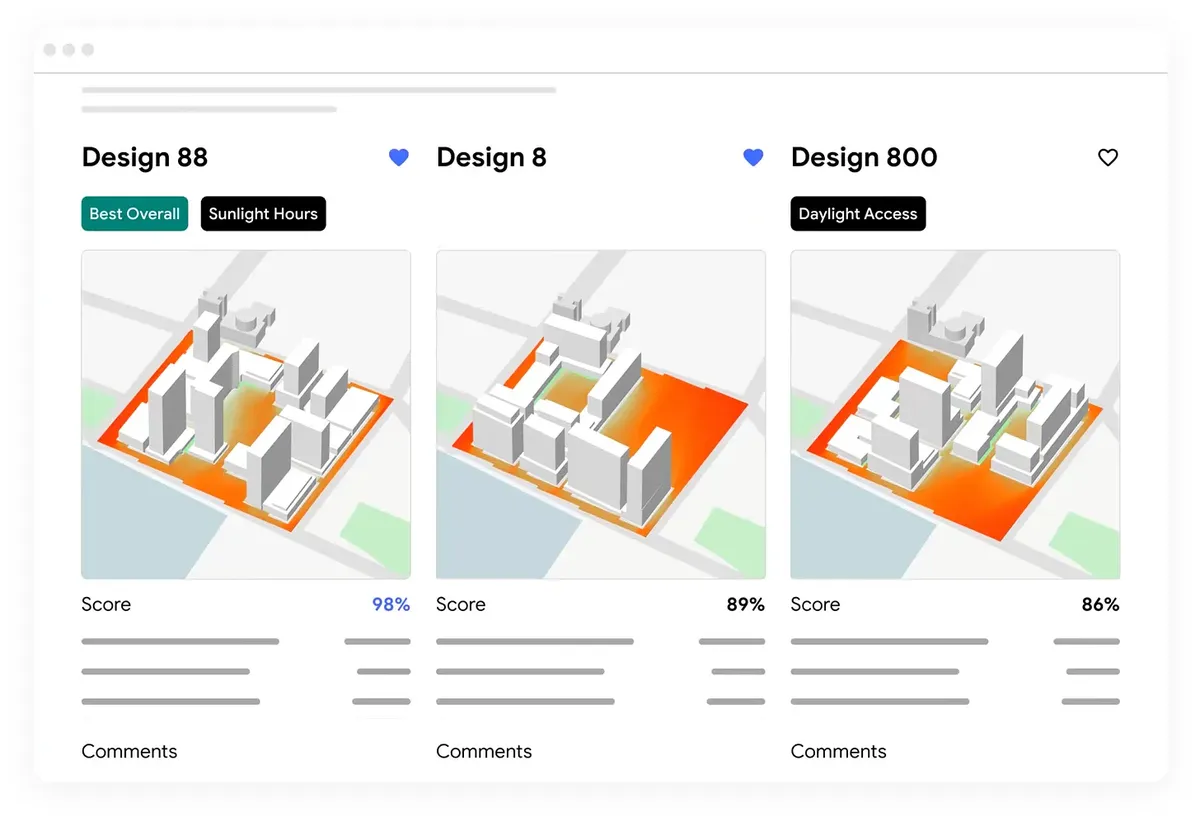

These sorts of ideas have developed into the philosophy of Design Optimization (DO). Using simulations, direct search, or genetic algorithms allows a designer to set constraints and goals and theoretically end up with the best possible option. However, reality does not work this way, as seen by the fact that less than 1% of buildings made today use DO as a major step in the design process.

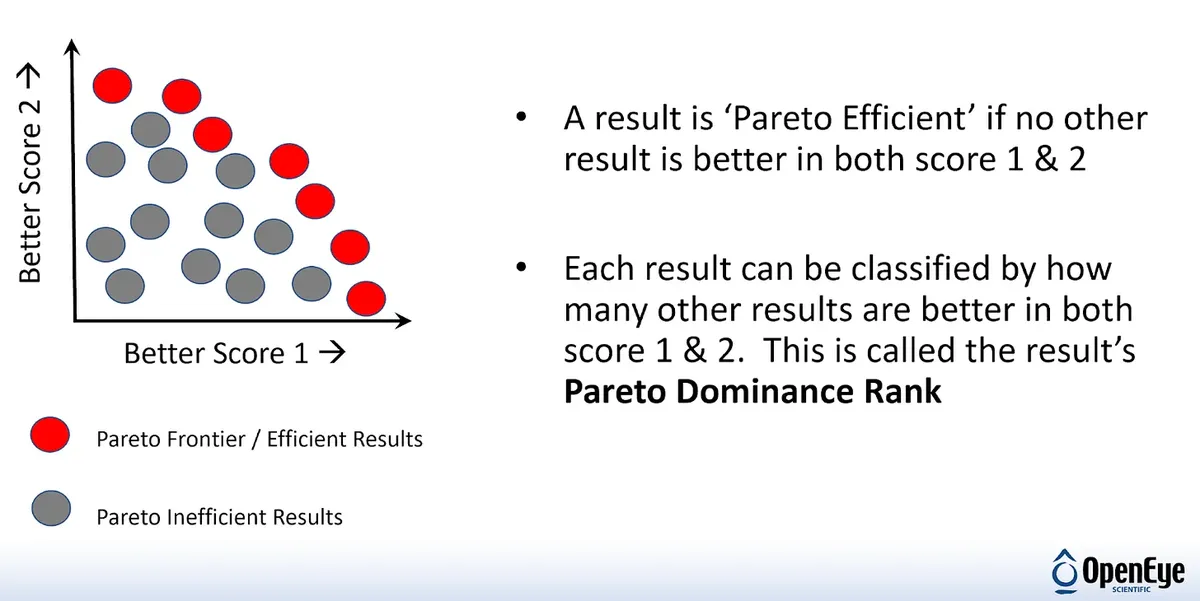

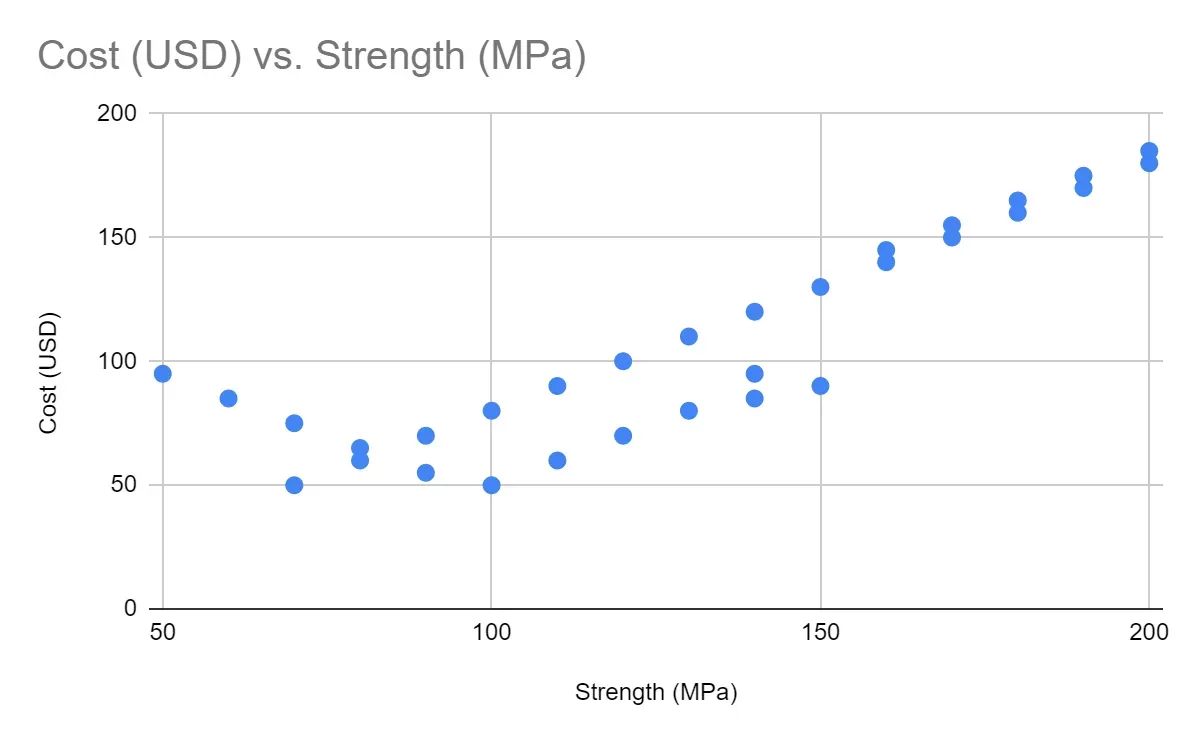

There is a lot to be learned about design and technology simply by breaking up DO into its component mechanical and philosophical parts. Let us imagine a hyper-simplified version to develop a mental model to use later. Assume being cheap and being durable are positive qualities that are inversely correlated and are the only two qualities that you care about in a building. Since these are our only two needs in the building, any material that is not either cheaper or more durable than another material is immediately not an option. This removes a very large portion of options (a good thing if you’re in Mr. Alexander’s camp of design thinking).

The list of all these materials that are the best “bang for your buck” exists at what is called the Pareto Frontier. This does not tell you what the best option is, but it does tell you what definitely isn't the best option.

A major argument against DO is that it is deterministic and removes creativity from the design process. Using our mental model, we can clearly see that this is not true. Choosing from the very large set of options along our Pareto Front is still a subjective choice. Is a $100 choice better than a $120 choice that is slightly stronger? You might suggest that there is a weighting that you can give to each dimension that would give you a clear answer, but this is subjective and begins to fall apart once you account for how many dimensions you’d have to actually account for.

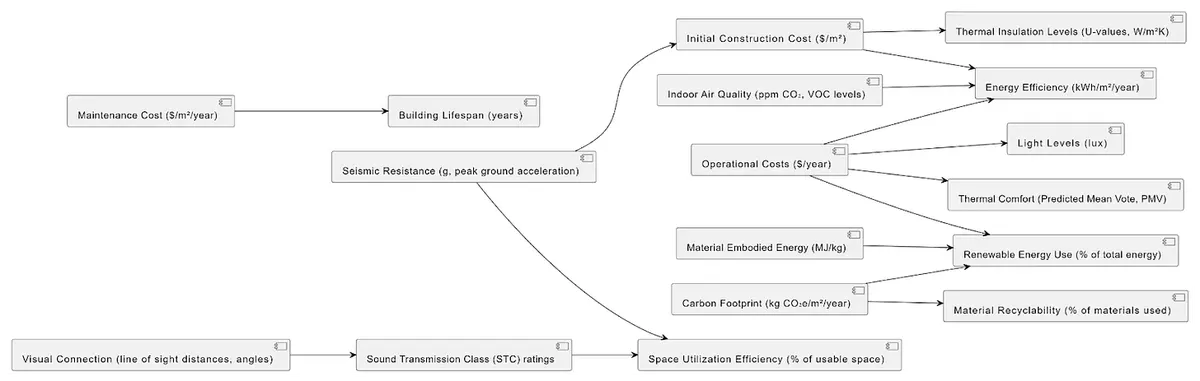

Here is a very quick and dirty list of negatively correlated dimensions that I made. As you can see, this becomes very complex very fast and leaves us as designers with near-infinite options that are all "optimal." However convincing you think the 2-dimensional model was, imagine a 17(?)-dimensional pareto front, full of bumps and local maxima and minima. The subjective choice of options from this slightly smaller infinity is the first argument for DO still counting as design.

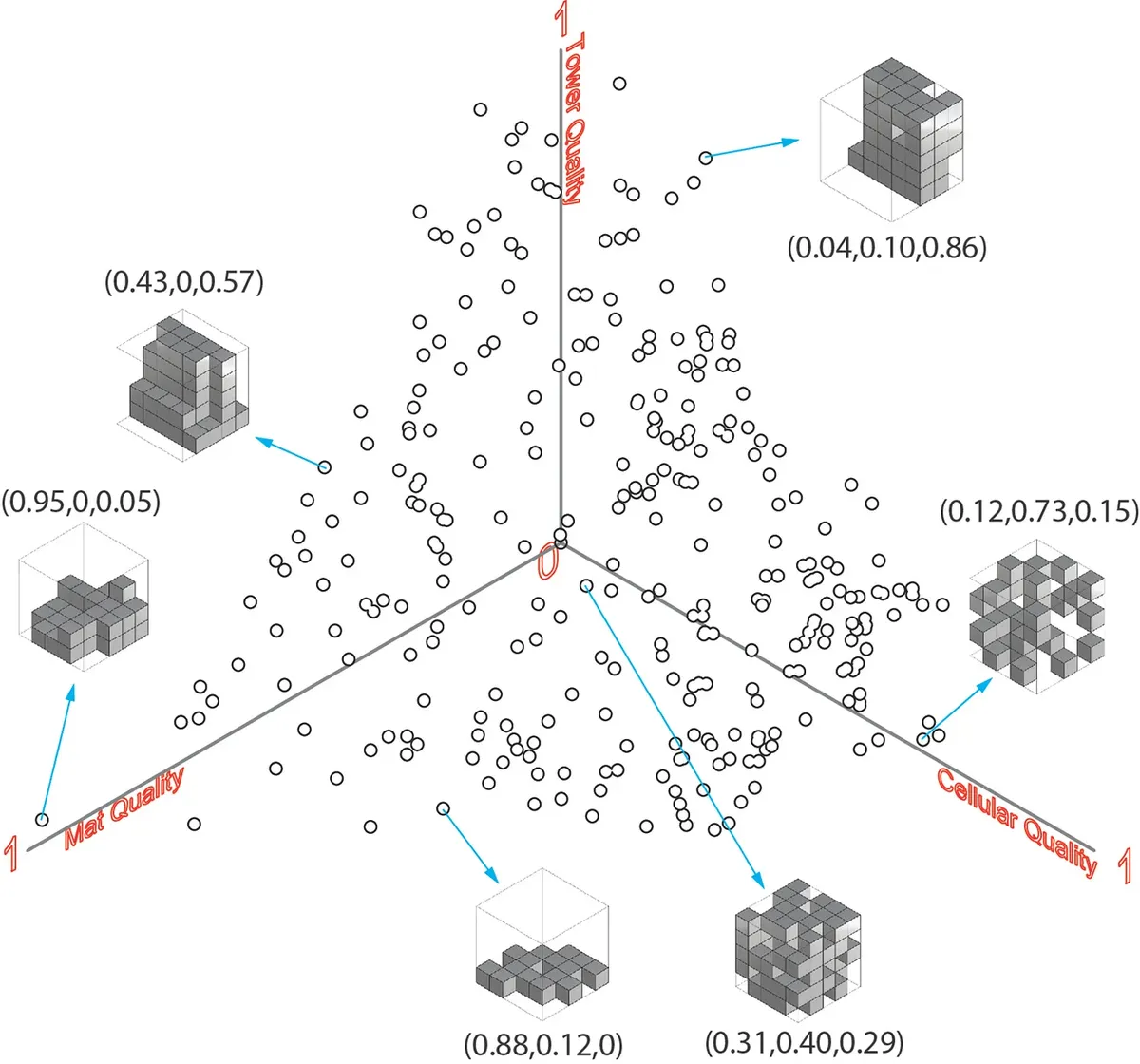

One layer removed from this abstraction, we now have to deal with the second argument for DO not being a solved problem. In the world of our simple mental model, we simply choose from a list of existing materials and plot them on our graph. In the world of form and design, we must contend with mapping all of these quantities onto spatial reality. The possible search space for “all forms that can fit in these set dimensions” is very large and does not neatly relate to any of our quantities. There are certainly heuristics that can help, but there's a reason genetic algorithms are often used, and these can often get stuck in local minima and can at best get within spitting distance of the actual Pareto front. DO, through something like a genetic algorithm, can give you a whole host of options to choose from, and even then, that is only a starting point.

Lastly, not everything regarding a design is quantitative. This is obvious but cannot be overstated. Even if you somehow had access to an alien supercomputer that gave you an impossibly optimized building, would you still build it if it was ugly? What is the ethical amount of efficacy you are allowed to trade for aesthetics? On one hand, this allows you to shorten your list of Pareto-efficient options to choose from. On the other hand, this is something else that you, as a designer, have to work on while attempting the difficult balancing act of good-fit design.

Products like Delve or Finch are not saviors of reasonable architecture and are also not useless cash grabs. They are simply private algorithms that turn an infinite design space into a smaller infinity. They might be useful productivity boosts, and they might not be. At the end of the day, the pareto front that is most important to you is the quality/time front. You must decide how much DO is worth using for you. That is the real design decision regarding optimization.